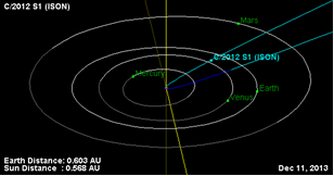

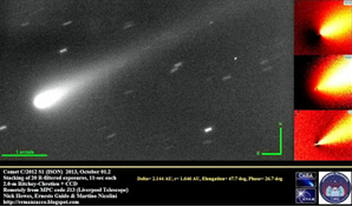

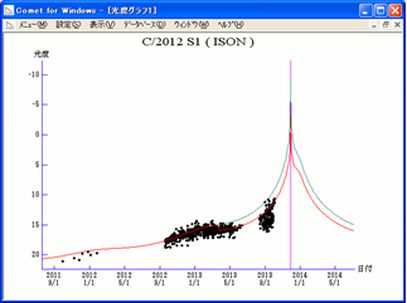

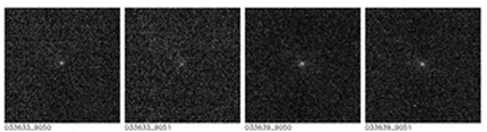

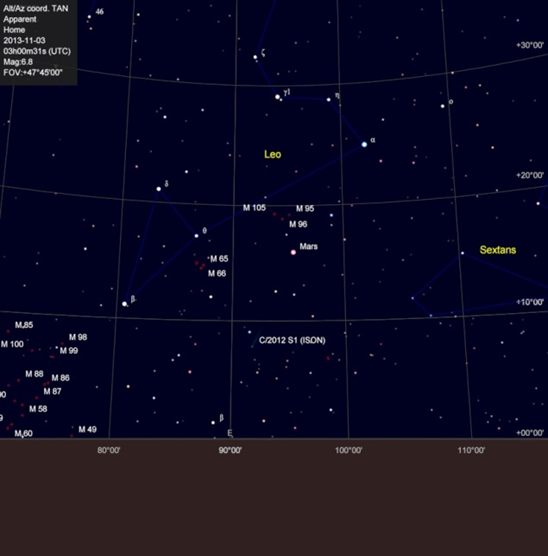

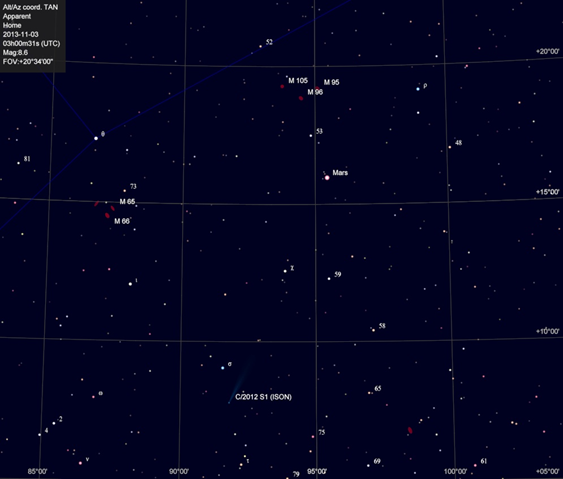

On the 28th of November the long awaited comet ISON (C/2012 S1) will reach perihelion (closest approach to the Sun). And we shall finally know if it is going to survive intact and give us a show to remember The comet was first discovered by Vitali Nevski and Artyom Novichonok, 2 Russian astronomers working with the International Scientific Optical Network (ISON) which is where the Comet takes its common name. At the time that it was discovered the comet was 6.29 AU from the Sun (1 AU = the average distance between the Earth and the sun which is around 150,000,000km or 93.2 million miles).  The comet is on what’s known as a hyperbolic trajectory meaning it is in a tight elliptical shape around our Sun. This suggests that it is a fresh comet from the Oort cloud, a hypothesized spherical cloud of icy debris left over from the formation of the solar system and lies around 1 light year from the Sun. Nearly quarter of the distance to the next nearest star. If the comet does survive its spin around the Sun it will be travelling fast enough to escape our Solar system never to return. The Comet was initially dubbed as the comet of the century as it was predicted at first to become very bright perhaps even bright enough to be seen during the day but as the comet has been getting closer and its brightness monitored it now looks as though it is going to fall below its initial predictions. This graph compiled by Seiichi Yoshida from Japan shows the comets initial brightness prediction as a blue line, the black dots show the measured brightness at different intervals and the red line is the current prediction which still is pretty good. Seiichi’s website has more information here and is well worth a browse! On October 1st comet ISON passed close to Mars at a speed of around 35 Km/s (80,000mph) and a distance of 10.5 million Km which is closer than it will get to Earth. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter took these images as it flew past. We have to keep in mind that both the orbiter and the camera were not designed to do this kind of work so it took a fair amount of effort to get these.  Ernesto Guido, Nick Howes, and Martino Nicolini captured this image of the comet as it was passing Mars using the 2 meter Liverpool telescope. It shows an already impressive tail and coma. Which the team state, was at 3 arc minutes in length. The comet is currently visible in small telescopes but you will need to be up early and have a good clear Eastern horizon to see it just before sunrise. This image shows the rough location on Nov 3rd at 3am UT by this time it will be just about inside the orbit of Earth continuing to accelerate towards the sun. At this point it is estimated to be around magnitude 7 but its by no means a certainty.  As we head on through November the comet will be getting closer and closer to the sun becoming a daytime object and unobservable and then, on the 28th of November at 18:32:38UT (JPL prediction at time of writing) it will come within 1.2 million miles of the sun’s surface. If it survives this very close encounter it will be flung around travelling at a staggering 845,000mph back out of the solar system and then hopefully the comet will become considerably brighter possibly visible with the naked eye and by mid to late December we will start seeing it at a more sociable evening time. The comet (if it survives) will make its closest approach to Earth on December 26th at a distance of 40 million miles. Let’s all hope that it does make it around the sun and give us something beautiful to observe and image but as for it being the comet of century? I guess we’ll have to wait and see. For more info about comet ISON visit www.cometison2013.co.uk Below I have added finder charts for early November. The comet will get lower each day.

0 Comments

Since starting in this hobby several months ago one of the things that have become evident to me is just how expensive it can be. Almost from the outset I started to want to photograph the things I was seeing to be able to share them with friends and family but the cost of the equipment put this beyond my reach, or so I thought.

Whilst looking into the basic techniques involved with astrophotography I stumbled across a well developed way of using everyday computer webcams to capture some pretty impressive images of the objects within our solar system and with modification can also be used to image objects much further away. Although there are lots of webcams on the market that can be used one standout model is the Philips SPC880NC which has had its software changed (flashed) to be the same as the older discontinued SPC900NC. I purchased one of these cameras complete as a Kit which came pre-flashed with a 1.25” nose piece and an infra-red filter which is easily attached and there are numerous “how too” guides on the net to help. The camera is inserted directly into the telescopes focuser with no need for an eyepiece (prime focus photography). I use 2 pieces of free software to capture and process images although there are lots of different ones out there it’s a case of finding what you’re comfortable with. Firstly SharpCap which I use to capture video footage from the webcam which is saved as an AVI file. The software has features that allow me to adjust the webcams setting in real time so the effects can be seen in the preview screen. There are also tools to help with focusing and the ability to convert the screen to night mode. Once I have my recorded AVI footage I load it into RegiStax which again is free to download and is used to stack the video footage and process the final image. The software will firstly look at the quality and alignment of the individual frames from the video and remove any that don’t meet your pre-set benchmark. It will then take your remaining frames and stack them on top of one another to create a single image. Once the image stacking is finished you can then adjust the brightness, contrast and sharpness to further bring out detail. I do then tend to use either paintshop or GIMP to further enhance or touch up the image. There is a surprising amount of free to download software available on the internet to give anyone an introduction into astrophotography without having to spend hundreds of pounds. Primers and tutorials are also easily found on the net for all of the processes I have mentioned. I think so far not including the telescope my entry into this side of the hobby has cost around £40. |

Steve BassettLiving on the South coast of England. Amateur astronomer Archives

July 2014

Categories

All

|

| Sompting Astronomy |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed